The Original Sin

Following Justice Ginsburg’s death a few weeks ago, there’s been a lot of hand-wringing around the so-called “McConnell Rule” regarding not confirming Supreme Court justices during an election year. This “rule” was invoked in early 2016, when Senator Mitch McConnell refused to hold a vote on President Obama’s selection of Judge Merrick Garland to fill Justice Scalia’s seat.

Calling this a rule, however, was always silly. It was never anything more than an excuse for the naked exercise of power (even if such an exercise of power flew in the face of long-standing norms and precedent). The unenforceability of the rule was apparent in 2016. What constitutes an election year? January of an election year? 365 days before an election? When the first exploratory campaign paperwork is filed with FEC? Should a second-term President ever be allowed to fill a Supreme Court vacancy? There was never any attempt to answer such questions, because the goal was political expediency, not enforceability or logic.

And yet Democrats persisted in the delusion that if a vacancy opened up in the final year of Trump’s first term, surely Mitch McConnell–man of his word that he is–would surely be bound by his own precedent. After all, what good is a rule if it is not applied in an even-handed and fair manner? But now on the precipice of what will almost certainly be the confirmation of Judge Amy Coney Barrett less than 16 days before the 2020 election, Democrats feel enraged as all pretense of principle has been stripped away, leaving bare the naked political ambition that was at the core all along.

Democrats (and I am one) should feel enraged. But at what? What was the original sin of our current Supreme Court predicament? Should we be upset that Mitch McConnell is not following the imaginary rule he created four years ago? As much as it saddens me that Donald Trump gets to dramatically alter the balance of power on the Supreme Court–something which will have lasting, negative effects for at least a generation–the President has every right to fill that seat with a nominee of his choosing. Democratic claims of hypocrisy are based either on the belief that the McConnell rule is in fact a rule or on the belief that the person who created the rule should be bound by it. In either case, being upset that McConnell is trying to fill Justice Ginsburg’s seat mere days before an election legitimizes and validates a practice that was wrong four years ago.

In that case, was the original sin the creation of the McConnell rule in the first place? Just as Donald Trump should get to fill Justice Ginsburg’s seat days before the election that could replace him, Barack Obama should have been able to fill Justice Scalia’s seat when Justice Scalia passed away 266 days before the election. Despite Mitch McConnell’s weak attempts at justification at the time, there is nothing in the Constitution or the country’s 240 year history that suggested otherwise. The McConnell rule was a norm shattering act of creative fiction. Democrats should have been enraged. Many were, but I suspect hubris tempered the reaction for many.

In the months leading up to the 2016 election, it was hard for many to imagine anything other than Hillary Clinton winning. This was more than just wishful thinking; on October 26–12 days before the election–one national poll¹ had Hillary ahead by 14% points. For many Democrats, it seemed like filling Justice Scalia’s seat was fait accompli. Hillary would win in November and would appoint Judge Garland or an equally qualified jurist, and engaging in parliamentary tactics to force a nomination through earlier would risk energizing conservative voters (in much the same way that Ginsburg’s death has activated Democratic voters this year). I think it was this hubris that prevented Democrats from being as angry as they should have been in 2016.

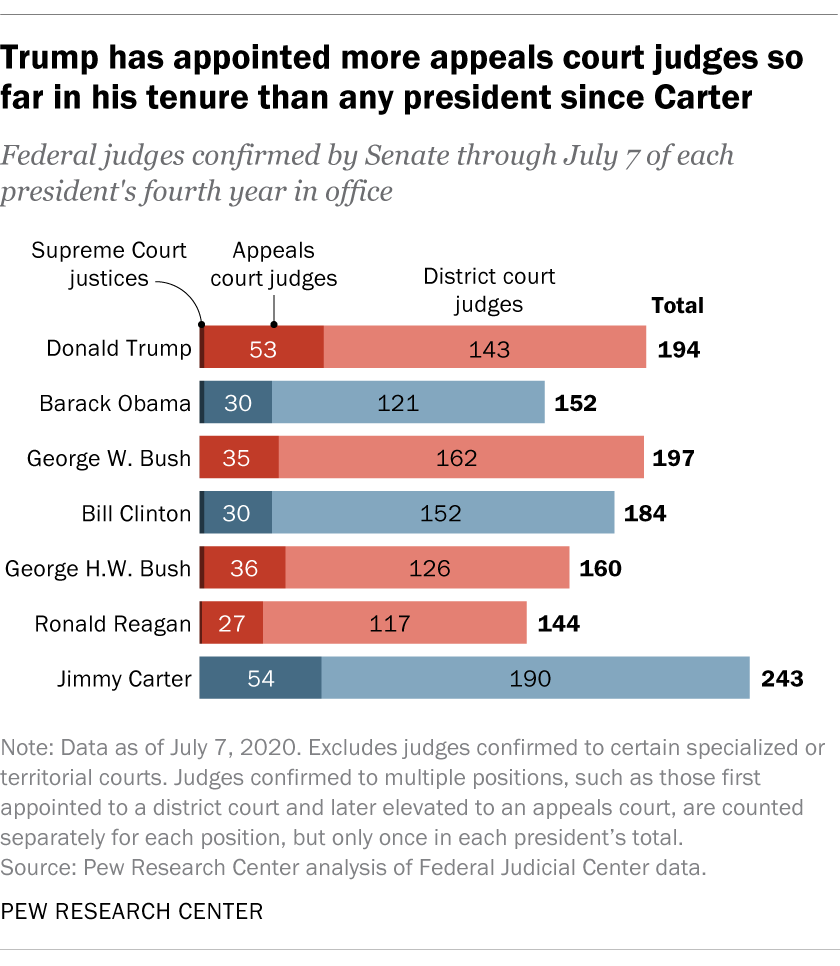

Although Democrats should have been more furious in 2016, this predicament did not start then. To understand the real problem, we have to look back even further–at the entirety of Obama’s presidency. According to Pew Research, During his eight years in office, President Obama appointed 312 judges to the federal bench. During three-and-a-half years, President Trump has appointed 194. The differences are more stark when you compare their records at same point in their terms:

This difference was no accident. It was part of an intentional campaign to hold open judicial vacancies until a Republican president was sworn in.

Just as it refused to consider Merrick Garland’s Supreme Court nomination, it shut down the lower court confirmation process. That’s water under the bridge. But documenting how the 114th Senate ratcheted up the contentiousness and polarization of an already broken confirmation process suggests how much harder it will be to ratchet it back into something with more comity and bipartisanship. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell now insists that there’s nothing “we can do …that’s more important … than confirming judges as rapidly as we get them.”

This situation did not start with Donald Trump or Merrick Garland. It was part of a years-long effort to politicize the courts. When Democrats float the idea of “packing the court” the GOP accuses them of politicizing the courts². The Democrats, in response need to make it clear that the original sin of politicizing the courts–whenever it started–certainly did not begin with court packing.

- It is concerning that Biden is performing comparatively worse, with national polls currently showing him only 8 points up, but there are reasons why the numbers may not be comparable.↑

- To be clear, I have very mixed feelings about the idea of court packing. Although it would serve to counterbalance the rightward shift in the short-term, it opens the door to a tit-for-tat endless packing.↑